, cg

Softimage Has Been Killed, the Future of CG Softwares Is Now in TD’s Hands

Softimage did shine in more than one’s heart until it met its fate with Autodesk. Our dear software is now dead but not our experience nor our vision. It’s now up to us to make the future brighter.

Softimage the Great

When I started to learn 3D on my own as a teenager, I used to play around with Maya 2.5. It looked complicated and unintuitive, which paradoxically excited me. Everyone within the online community that I was frequenting found it hard to use. I liked the challenge. And the splashscreen too.

I kept reading good reviews about the recently released Softimage|XSI and decided to try it out one day. I gave up 30 minutes after opening it. I didn’t like the default shortcuts, I didn’t like the UI. I didn’t give it a chance.

It’s only when I got in touch with Action Synthèse in 2005 that I got back into it. I had no other choice if I wanted to land an internship anyways. For that reason I took the time to setup my own shortcuts, to get used to the UI, and to get some sensations going.

It didn’t take long, it was a blast. I realized how stupid I was to give up so easily before.

My goal was to learn rigging and it was the best tool for that. There was nothing preventing me from applying my ideas—Softimage had a fast learning curve, it was intuitive, and made perfect sense. Thanks to that in no time I felt comfortable to get some rigs going.

I never wrote any line of code before then but I thought it would be a good idea to also learn how to develop. That’s how I started to use the Softimage SDK. I struggled quite a bit at understanding how to write my code in the first place but the API itself was no problem. Here again, everything made sense, even for a total beginner like me, and I quickly got my first scatter tool going.

Some softwares are simple to use but don’t get you very far. It wasn’t the case with Softimage. Thanks to its well-thought architecture, it never got on the way when complex work was required.

On top of the quality of the software itself, both the developers and the community were forming a great symbiosis. That was a bunch of active, friendly, helpful, and innovative souls. Softimage was driven by its users. Everyone was involved.

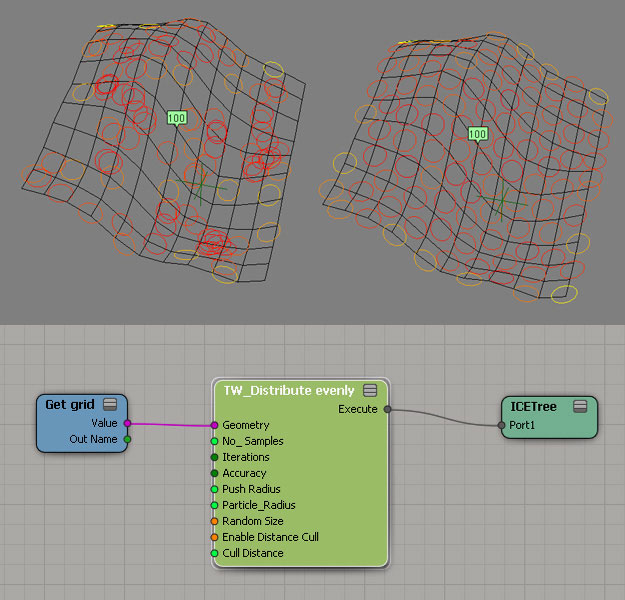

With the implementation of the nodal graph ICE in July 2008, things quickly became out of control. More power at the reach of every artist. Everyone had a blast using it, countless of inspiring demonstrations of the tool kept emerging on the Internet. It also quickly became indispensable.

a Softimage ICE compoundcredit: Benjamin Paschke (with permission)

a Softimage ICE compoundcredit: Benjamin Paschke (with permission)

The Struggles

Eventually Autodesk felt the threat coming and perceived Softimage as a strong competitor to Maya and 3DSMax. Four months after the public release of ICE, Autodesk bought Softimage from Avid. A that point, they owned the 3 major all-rounded 3D softwares on the market. No more competition on this front.

As soon as the deal got rumored, things started to change. The community grew concerned and unsecure about the future of its software. The Softimage public mailing-list became the place of numerous heated debates on the subject.

But the community was stronger. It regained optimism when seeing the work accomplished by its users. Two of them mainly ended up doing the show and managed to open the eyes of those living on the planet Maya. They both developed plugins for ICE: Eric Mootz with his Mootzoid nodes and Thiago Costa with Lagoa Multiphysics.

test of emTopolizer2credit: Tim Borgmann (with permission)

test of emTopolizer2credit: Tim Borgmann (with permission)

We were proud to be Softimage users even though we started to feel more and more abandoned by Autodesk after each new release. Softimage was marketed as a plug-in for Maya, had less features implemented, the developers eventually moved to the Maya team, and always more debates were being fired up on the list.

Meanwhile I was dealing with my own struggle in parallel.

I landed a job at Weta Digital and had to learn Maya. I tried hard to approach this transition from an open-minded pespective and there was no big issue in transferring my rigging skill set. The concepts in rigging are pretty much the same everywhere. What dumbstrucked me was the process to get to that same result.

I felt like I was back to stone age. I found many of Maya’s daily tasks and the design of its API to be retarded. I spent my first weeks (months?) asking my teammates how they could possibly work with a such software. Even now, I still refuse to do in Maya a task as simple as painting some skin weights. It drives me crazy.

My colleagues wouldn’t understand my frustration. All they knew was Maya, they couldn’t compare it to anything else. I was being just annoying to them. I sometimes wished to be ignorant too—it would have helped with my zen.

But at the end of the day, let’s face it. As good as Softimage could be, it was a battle lost in advance. They’ve been trapped.

The Proprietary Do-It-All Trap

One size doesn’t fit all. All-rounded 3D softwares cannot please the specific requirements of each studio and each user, and that’s fair enough.

Keeping a such package up-to-date is not guaranteed neither. Developers cannot afford to focus actively and simultaneously on each area covered by this kind of software. The large codebase, the deep dependencies between each internal module, and the unique core architecture and data structures trying to accomodate each discipline are all not helping much here.

Specialized softwares are more likely to remain competitive by implementing the latest technologies in their field and even define new standards themselves. But then those all-rounded 3D packages allows for a smooth pipeline out of the box. For a company just starting its business and not having much resources yet to invest in RnD to connect the dots of a more flexible pipeline, this has always been an attractive feature.

I believe this was especially a game changer back in the 90’s when anything must have been a struggle. If a unified pipeline with a single software could make the life of its users a bit simpler, then what could be wrong with that?

That’s how most studios ended up buying a single package and decided to fill the holes by developing in-house tools. This task was furthermore eased with the developers not having to worry about implementing math, geometric and other complex libraries. It was already all there, available directly within the APIs built-in into the softwares. Developers could focus on getting their tools to work within their tight deadlines.

But that’s also where the bottleneck lies. Using those APIs meant that all the code being written would be gravitating around a proprietary software, creating deep dependencies with it.

Once a studio has invested years in developing tools, workflows, and a pipeline for a specific package, it becomes difficult to change ship. They’re stuck with it, for the best and for the worst.

In this context, there’s no point for a studio to move from one package to another, especially if it is to end up in the same situation a few years later. Since Maya has always been on top of the film industry market, there was no hope for Softimage to gain much more seats from the large studios.

Hence the decision of Autodesk to discontinue it.

That’s life but I can’t help thinking that they’ve planned it all since the begin because it kinda make sense from a business point of view: buy Softimage to get rid of the competition, move its features to Maya who’s leading the market, and kiss goodbye to everyone relying on it for their living because Autodesk can’t afford maintaining its development.

Nice hypocrital move after repeating years after years that they wouldn’t kill it.

The Modularization Has Already Started

Some studios grew tired of having their invested development being so closely tied to the unknown future of a software that they didn’t own.

They started to cut their bounds and to regain some control by creating their own file formats or using standardized ones. The main idea being to store their data in a generic way to make it easily transferable onto any software. The native software’s file formats were only to be used by the artists to save their work in progress before publishing.

With this in place, it was then possible to split the pipeline into logical chunks. Each department could work on the software(s) of their choice as long as they could output the data in the expected format. I’ve even seen 3 different softwares being used in the FX department on a same show. The right tool for the right job.

The way to write tools itself has also changed to be done in a more modular and portable fashion. If you’ve spent years to develop a full-on muscle system but made it highly dependant on Maya’s API, then you’ve exposed yourself to rewrite pretty much the whole thing if you decided one day to port it onto another software. Instead, the goal here is to split the core with its gateway connecting it to the target software. Got a new software? You’ve only got to write a new gateway to plug the core in.

To take full control over the destiny of a tool, some of the largest studios went for the next level. They developped stand-alone fully-featured applications. It is a tremendous work in terms of development and maintenance but in a world of closed-source softwares this is after all the only viable solution to ensure a long-term vision with an active development focused on the specific requirements of a studio.

That was it. Some pioneers did their first steps towards independance.

TDs Can Now Shape the Future

Ideally each studio should have adopted a such modular approach to tools development. The trend being to implement deformers, simulation nodes, rigs and other involved developments into an in-house stand-alone nodal graph platform to then glue its content with different softwares.

Of course, not everyone could push for that. Not until now.

That’s where new solutions such as Fabric Engine come in.

Fabric Engine shines at abstracting the complexity of writing portable code. It allows any developer, including TDs, to write their tools in a stand-alone nodal graph and to painlessly make them usable in every software. Code it once, use it everywhere. All this with maximum performances out of the box.

Now, imagine the talented community of TDs and developers joining their forces to build a library of tools and making them accessible to everyone on an App Store-like platform.

Tools such as Gator, Lagoa Multiphysics, emPolygonizer, Unfold 3D, and more, would be available to everyone on every package. And ICE? Well, that’s already part of Fabric Engine 2.0.

If that library of tools managed to encompass the needs in each area of CG, then the one requirement left to buy a software would be to have a hosting environment for Fabric Engine. It would become used simply as a shell where the main selling argument would be a good UI/UX to perform efficiently daily tasks.

With Fabric Engine also providing a set of extendable modules to assist building applications, including a powerful real-time renderer and a set of extandable Python UI widgets such as an OpenGL viewport, an animation timeline, and so on, another choice would be for the users to assemble themselves their own hosting application.

How much more powerful and dynamic would our toolset become if it was directly driven by its community, if we were all contributing to shape the future of CG softwares?

If the entire userbase started to break its dependencies with today’s softwares, Autodesk would lose the control of the market and it would be our turn to kiss them goodbye.

I’d say it’s the way to go anyways. Theorically it opens the doors to a longer-term vision and its team is made of a good bunch of passionate souls. It’s worth giving it a go, let’s just hope that Autodesk won’t buy them out.